The Fyre Festival and the Trumpet of Amplification

Author: mikecaulfield

Go to Source

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’re probably aware that there are two documentaries out on the doomed Fyre Festival. You should watch both: the event — both its dynamics and the personalities associated with it — will give you disturbing insights into our current moment. And if you teach students about disinformation I’d go so far as to assign one or both of the documentaries.

Here is one connection between the events depicted in the film and disinfo. There are many others. (This post is not intended for researchers of disinfo, but for teachers looking to help students understand some of the mechanisms).

The Orange Square

Key to the Fyre Festival story is the orange square, a bit of paid coordinated posting by a set of supermodels and other influencers. The models and influencers, including such folks as Kendall Jenner, were paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to post the same message with a mysterious orange square on the same day. And thus an event was born.

People new to disinformation and influencer marketing might think the primary idea here is to reach all the influencer followers. And that’s part of it. But of course, if that were the case you wouldn’t need to have people all post at the same time. You wouldn’t need the “visual disruption” of the orange square.

The point here is not to reach followers, but to catalyze a much larger reaction. That reaction, in part, is media stories like this by the Los Angeles Times.

And of course it wasn’t just the LA Times: it was dozens (hundreds?) of blogs and publications. It was YouTubers talking about it. Music bloggers. Mid-level elites. Other influencers wanting in on the buzz. The coordinated event also gave credibility required to book bands, the booking of the bands created more credibility, more news pegs, and so on.

You can think of this as a sort of nuclear reaction. In the middle of the event sits some fissile material — the media, conspiracy thought leaders, dispossessed or bitter political influencers. Around it are laid synchronized charges that, should they go off right, catalyze a larger, more enduring reaction. If you do it right, a small amount of social media TNT can create an impact several orders of magnitude larger than its input.

Enter the Trumpet

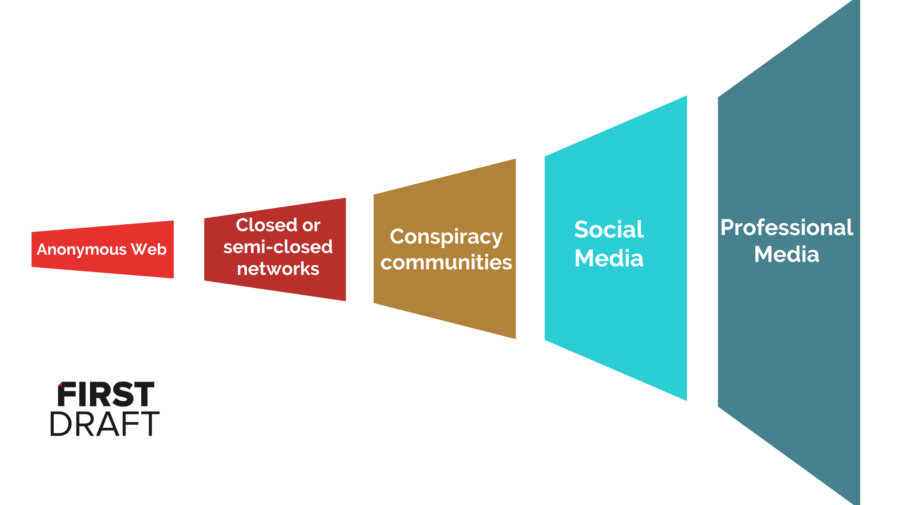

Central to understanding this is the fissile material is not the general public, at least at first. As a marketer or disinfo agent you often work your way upward to get downward effects. Claire Wardle, drawing on the work of Whitney Phillips and others, expresses one version of this in the “trumpet of amplification“:

Here the trumpet reflects a less direct strategy than Fyre, starting by influencing smaller, less influential communities, refining messages then pushing them up the influence ladder. But many of the principles are the same. With a relatively small number of resources applied in a focused, time-compressed pattern you can jump start a larger and more enduring reaction that gives the appearance of legitimacy — and may even be self-sustaining once manipulation stops. Maybe that appearance of legitimacy is applied to getting investors and festival attendees to part with their money. Or maybe it’s to create the appearance that there’s a “debate” about whether the humanitarian White Helmets are actually secret CIA assets:

Maybe the goal is disorientation. Maybe it’s buzz. Maybe it’s information — these techniques, of course, are also often used ethically by activists looking to call attention to a certain issue.

Why does this work? Well, part of it is the nature of the network. In theory the network aggregates the likes, dislikes and interests of billions of individuals and if some of those interests begin to align — shock at a recent news story for example — then that story breaks through the noise and gets noticed. When this happens without coordination it’s often referred to as “organic” activity.

The dream of many early on was that such organic activity would help us discover things we might otherwise not. And it has absolutely done that — from Charlie Bit My Finger to tsunami live feeds this sort of setup proved good at pushing certain types of content in front of us. And it worked in roughly this same sort of way — organic activity catches the eyes of influencers who then spread it more broadly. People get the perfect viral dance video, learn of a recent earthquake, discover a new opinion piece that everyone is talking about.

But there are plenty of ways that marketers, activists, and propagandists can game this. Fyre used paid coordinated activity, but of course activists often use unpaid coordinated activity to push issues in front of people. They try to catch the attention of mid-level elites that get it in front of reporters and so on. Marketers often just pay the influencers. Bad actors seed hyperpartisan or conspiracy-minded content in smaller communities, ping it around with bots and loyal foot soldiers, and build enough momentum around it that it escapes that community. giving the appearance to reporters and others of an emerging trend or critique.

We tend to think of the activists as different from the marketers and the marketers as different from the bad actors but there’s really no clear line. The disturbing fact is it takes frightfully little coordinated action to catalyze these larger social reactions. And while it’s comforting to think that the flaw here is with the masses, collectively producing bizarre and delusional results, the weakness of the system more likely lie with a much smaller set of influencers, who can be specifically targeted, infiltrated, duped, or just plain bought.

Thinking about disinfo, attention, and influence in this way — not as mass delusion but as the hacking of specific parts of an attention and influence system — can give us better insight into how realities are spun up from nothing and ultimately help us find better, more targeted solutions. And for influencers — even those mid-level folks with ten to fifty thousand followers — it can help them come to terms with their crucial impact on the system, and understand the responsibilities that come with that.