Johns Hopkins students escalate sit-in over proposed campus police force

Author: Jeremy Bauer-Wolf

Go to Source

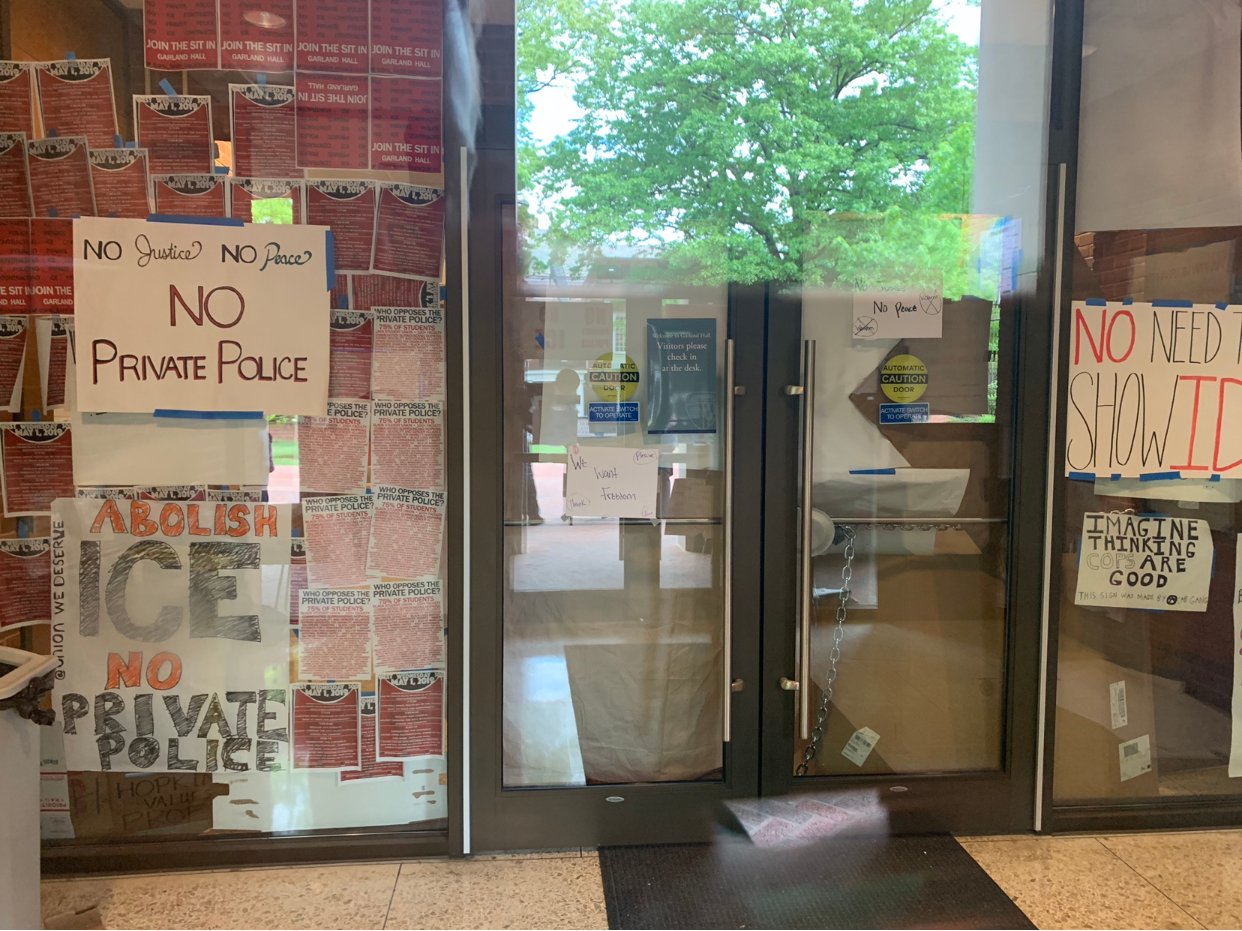

People at the Johns Hopkins University campus can’t walk into the main administrative building, because student protesters have chained its doors shut.

Security stands outside and posters paper the doors and windows — one reads “No Justice, No Peace, No Private Police.” The main entrance is obscured with fliers detailing opposition to the university’s plan to bring its own police force to the elite private institution in Baltimore.

The bleak setup conveys the tensions that have escalated between student activists and administrators in the past month. Critics of the police proposal have overtaken Garland Hall, saying that private, armed law enforcement would bring a host of issues. Students have spoken out about the risk of violence and racial profiling, a concern that other colleges and universities have encountered when attempting to beef up their police presences.

Especially in the last several years, campus police officers have been criticized for their handling of racial incidents and students with mental health issues — students elsewhere who are suicidal or experiencing psychotic episodes have been shot dead by police. Last month, a black couple, unarmed and fully compliant during a traffic stop, was shot by police near Yale University (not fatally). One of the officers was from Yale’s department, prompting protests that shut down two campus thoroughfares.

Hopkins currently uses a group of off-duty Baltimore City police, who would be replaced with sworn university police.

Ronald J. Daniels, president of Hopkins and target of the students’ ire, had initially said he would not meet with them as long as they occupied the hall, calling their presence a safety hazard that has forced the university to either relocate or temporarily discontinue services such as financial aid and academic advising.

Daniels on Sunday did agree to sit down with the students — but it’s unclear whether this would ultimately change the outcome. The university has heavily lobbied state lawmakers for a police force, saying that it was needed to mitigate crime close to the campus. The Legislature passed, and Republican Governor Larry Hogan signed into law last month, a bill authorizing the force, which was needed given Hopkins is a private institution.

Public colleges in Maryland — Morgan State University and Coppin State University, among others — already have their own police.

“Rather than taking responsibility for the harm inflicted on our community, President Daniels and his administration have chosen to willfully ignore our concerns while directing the vast resources of the university to further entrench a climate of fear, intimidation and surveillance,” the student protesters wrote on Facebook.

The protests began in early April, over a prospective police force and the university’s contracts with oft-criticized Immigration and Customs Enforcement that total $1.7 million. These contracts, which expire this year, largely are for educational programs in law enforcement leadership and emergency medical training, and aren’t related to immigration enforcement.

The protests began in early April, over a prospective police force and the university’s contracts with oft-criticized Immigration and Customs Enforcement that total $1.7 million. These contracts, which expire this year, largely are for educational programs in law enforcement leadership and emergency medical training, and aren’t related to immigration enforcement.

An initially small contingent of student protesters and other advocates grew into hundreds piling into the hall that also houses Daniels’s office. Garland remained open until this month, when students raised the stakes. They chained themselves to walls, railings and staircases, refusing to leave until administrators negotiated with them.

Students forced a complete shutdown of Garland Hall, and it has been converted to a makeshift den for the core activists who eat, live and work there most of the time. Almost all the doors are chained shut, but not one connected to the president’s office. One student told a reporter at the building that Daniels still hasn’t been spotted and that he’s “probably afraid of black people.”

Snacks — chips, a bulk quantity of Jolly Ranchers — litter the spaces in the lobby. One table was set up with Chipotle, catering style. One of the hall dwellers said that it’s partially paid for by donations, including from a GoFundMe that has raised more than $2,700.

Banners are hung from stairs. The largest reads, “No private police. No ICE contracts. Justice for Tyrone West.”

West was a black Baltimore man — unaffiliated with Johns Hopkins — who died in 2013 after an altercation with Baltimore City police. He fled from a traffic stop during which officers found cocaine, and the resulting struggle when police caught him resulted in his death. Officers weren’t charged in West’s death, but his family received a $1 million settlement from the city and state.

The students want the university to marshal its resources and help victims of police brutality, they said in interviews.

Turquoise Baker, one the students who is leading the campaign, said as a black woman she and other students have experienced racial profiling. She noted that Baltimore City police have poor “bedside manner” — indeed, the department has a long history of tense relations with the community. The 2015 riots over racial injustice and police use of force in Baltimore were in part inspired by the death of Freddie Gray, a young black man who died in the custody of six Baltimore officers.

Baker theorized that the push for armed officers wasn’t the result of any spike in crime, but rather the administrator’s desire to improve the campus image to potential parents and donors.

“Our goal is to try force them to pay attention, not only listen but acknowledge,” Baker said of college leaders.

Cyril Creque-Sarbinowski, a graduate student and another organizer, said that administrators, specifically Daniels, have been “dismissive” of the movement, which forced the students to ramp up their efforts and fully occupy the building. He said that Daniels would walk by the group in Garland Hall and deliberately avoid speaking, or making eye contact, and if Daniels did make a remark, it was snide.

“It was never truly an earnest discussion,” Creque-Sarbinowski said. “They were treating us as a problem that would go away eventually.”

Daniels wrote a letter to campus on May 3 saying that the protesters must bring their activities “in line with legal requirements and university guidelines” before he would meet with them. The university wrote in an earlier message that disrupting “events and services” violated campus policy, but did not say whether students would be punished. A spokeswoman did not respond to a request for comment, including whether officials intended to discipline the protesters.

“Reasoned, analytical and open debate is the hallmark of our university community. As this academic year comes to a close, we have an opportunity to reaffirm our commitment to these ideals, even when it appears that the differences in our positions on the issues we care about seem large and unbridgeable,” Daniels said in his letter. “Perhaps through open, generous conversation we can find glimmers of understanding that surprise us all. In a time of so much national discord and polarization, that would be truly uplifting.”

After the bill to form the police force passed the Legislature, Daniels sent a message to campus, saying it addressed an “urgent” need around increased crime on and around the Hopkins campuses.

“We believe in the end that this legislation reflects an approach to university and community safety that we can be proud of at Johns Hopkins and in Baltimore, setting a standard as the most comprehensive set of university policing requirements anywhere,” Daniels said in his statement. “Yet we also know that the true test of this effort lies ahead, as we begin the work of building a constitutional, community-oriented and publicly accountable university police department, with fidelity to the letter and spirit of this law.”

On Sunday, Daniels reversed course and agreed to meet with the protesters and have the gathering live-streamed.

But the students wanted assurances — including that a neutral, mutually agreed-upon mediator would conduct the negotiations and that students, professors and staff who participated in the protests wouldn’t be punished. They also wanted to be let back into the building and not be arrested if the talks went awry.

The campus police force, if it comes to fruition, would patrol the main grounds, called Homewood, as well as the Hopkins medical campus and the Peabody Institute. The law allows Hopkins to have a force of up to 100 armed officers.

The law, which also requires the officers to wear body cameras, had widespread support among legislators — the final vote in the Senate was 42 to 2.

Other colleges have been criticized when attempting to hire police. Student groups at the University of Rochester protested adding armed officers last year, calling the move “disheartening” for minority students. Evergreen State College was condemned for trying to add two police officers last year, too, after cutting faculty positions.

Kushan Ratnayake, another protester, said he is confident that the coalition will be successful. He pointed to recent student victories with sit-ins at Swarthmore University, where students occupied a fraternity house for days over accusations of sexual violence before the two campus fraternity chapters disbanded.