Loyola faculty group is pushing back against major cuts to its English language learning program

Author: Colleen Flaherty

Go to Source

Faculty members at Loyola University Chicago criticized the university for abruptly firing all of its English as a second language instructors, full- and part-time, last spring. The terminated professors at the time understood that they were being let go because the language program was ending. Yet the university has since insisted that the program never closed and, citing fluctuations in international student enrollment, says that it’s now operating on a scalable staffing model.

That may be true: the university retained one full-time employee to both direct the program and teach it, and enrollment numbers are now low. But a new report from the Loyola chapter of the American Association of University Professors says low enrollment resulted from cuts to the program, and that the university’s move has cost money and prestige, not saved any.

The AAUP is “greatly concerned about the university administration’s failure to appropriately staff oversight of global engagement, the precipitous decline that has occurred in international enrollments over the past three years, and the decimation of Loyola’s English Language Learning Program,” reads the report. “This negligence, as well as direct actions taken against international programming, have compromised Loyola’s ability to serve important parts of its mission.”

These actions “have harmed our financial bottom line and fiscal vitality,” the report also asserts. “And this dramatic reversal of course has taken place outside of the established channels for academic decision-making laid out in Loyola’s own procedures” and widely followed, AAUP-recommended governance practices.

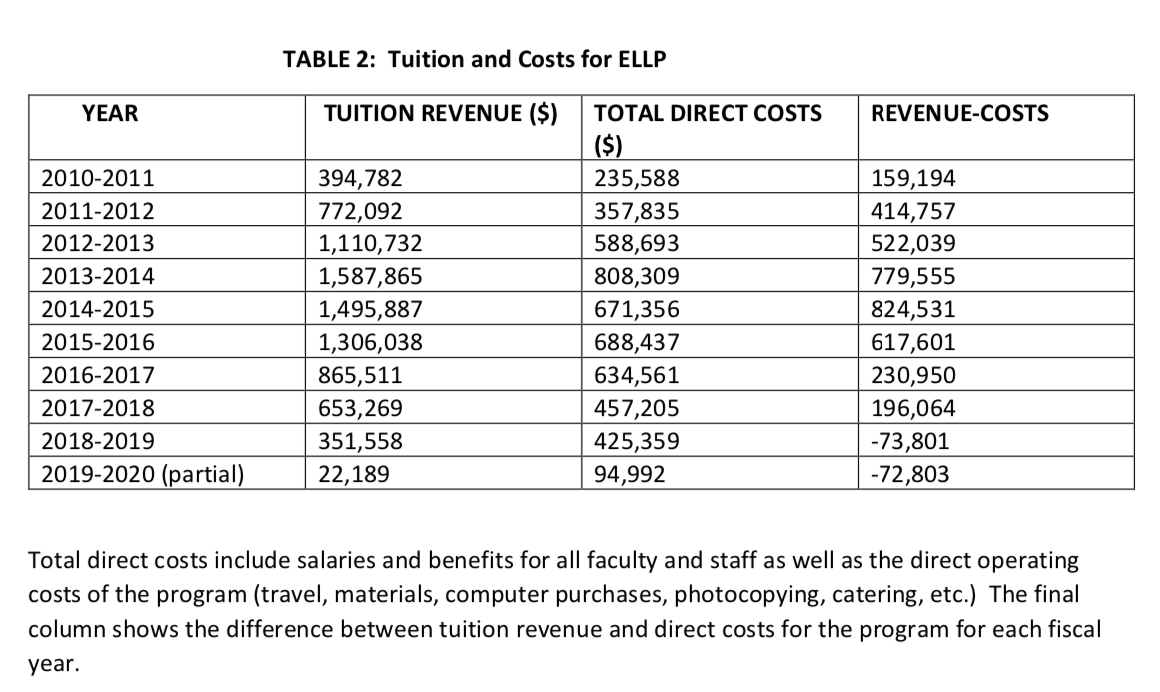

By the AAUP’s calculations, Loyola’s decisions regarding the English program have cost the university at least $200,000 in net revenue over a year, and perhaps much more in terms of lost opportunities to attract international students.

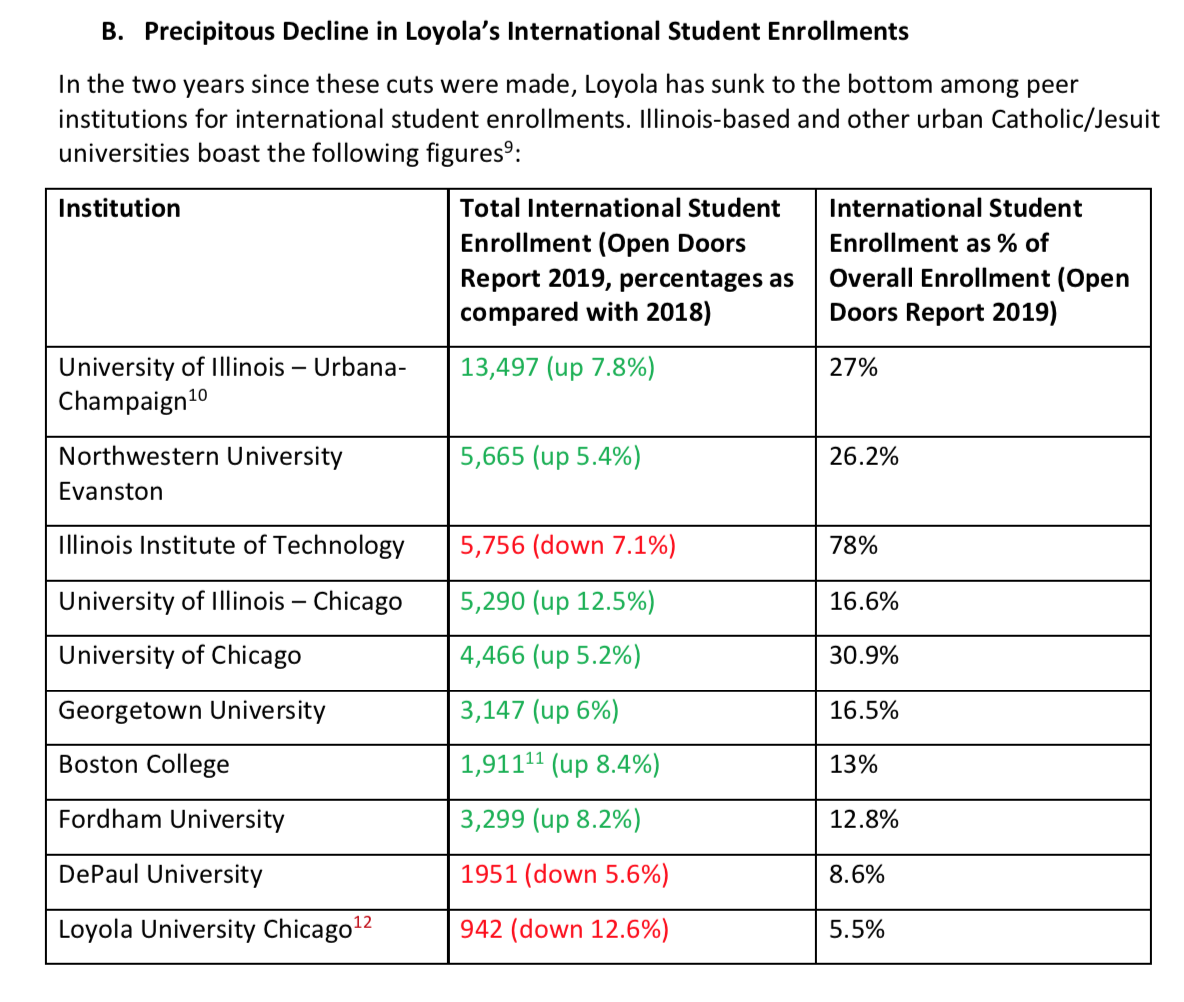

The disinvestment in international programs also pushed Loyola well below peer institutions on several international enrollment metrics, the report alleges.

Michael J. Kaufman, dean of law and vice provost at Loyola, said in a statement the university and its administration remain “very dedicated to global education and engagement.” He said the report contains errors of fact and concept but that he would need more time to process it to respond in depth.

Faculty Reactions

Linda Rousos, a former instructor in Loyola’s program, said of the report, “I’m so happy that we continue to have so much support from the AUUP and from the faculty, and their understanding of how important international programs and ESL are, because that certainly wasn’t the case from the administration.”

Loyola “really needs to allow international students to come as full-time English students,” she added, “because without them, they’re giving up revenue and all of the benefits that come from having international students, especially those who would eventually enroll [in the university].”

At Loyola, where she taught part-time for five years after a long career teaching full-time elsewhere, Rousos taught English language learners fresh out of high school, to graduate students, to those who already had advanced degrees but who understood English to be the common international language for business, science and research and wanted to improve. Beyond having great students, what still stands out to her about Loyola’s program was how good it was.

“Assessing students’ progress in language learning, in speech, reading and writing, is really challenging, and to standardize and calibrate it across faculty so that we’re all looking for the same things,” recalled Rousos, “a lot of programs don’t have that down, but Loyola really did.”

Rousos said she never saw or heard about administrators visiting the language center to see the work being done or to meet students, either, making the decision to clip the program all the more “senseless.”

“One problem the administration had was understanding that there are different kinds of ESL programs,” she said, “and they had no idea our program was about academic preparation. We’re having students detect bias in research articles and writing summary responses and doing endnotes and citations and listening comprehension,” she said. “We coordinated with the content areas and worked really well with other faculty, too.”

Amy Shuffelton, an associate professor of the philosophy of education at Loyola, who did not help write the AAUP report, said having a well-resourced English language learning program is vital because it makes it “possible to attract and retain more international students.” As U.S. institutions face an enrollment cliff, with a projected decline in the traditional college-age population, other counties — including Vietnam, where Shuffelton recently visited with her international higher education class — have the opposite problem, she said: too many would-be students for too few available, quality university seats.

“If you look at global trends, it’s a no-brainer,” Shuffelton said of investing in the English language learning program. “We need international students because they add to the caliber of our classes, but also because — more hard-nosedly — we need their tuition dollars.”

If Loyola doesn’t admit these students and retain them, through strong English language programs that support academic quality across the university, she added, “other institutions will.”

Internally, Loyola has attributed some of its actions to documented national declines in international undergraduate student enrollments since these numbers peaked in about 2015. Last year, for instance, according to the “Open Doors” survey, the number of international undergrads declined by 2.4 percent nationwide, while the number of international graduate students declined by 1.3 percent and the number of international nondegree students declined by 5 percent.

Many have attributed this decline to the U.S. political environment surrounding immigration.

At the same time, the total number of international students in the U.S. increased slightly last year, by 0.05 percent, due to a 9.6 percent increase in the number of international students participating in an optional visa program.

The AAUP report also makes the case that the answer to the international student enrollment question is not to give up on them but to reinvest in recruitment and support services that will make them feel welcome.

A History

Earlier this academic year, professors at Loyola said the English program changes were among their many growing concerns about shared governance at Loyola. The focus of the ire then was a similarly abrupt change to their health-care plans. This new AAUP report — compiled with input from former program staff members, university documents and other data — gives much more insight into what’s happened to the language program, however.

The AAUP review begins in late 2018, when Loyola announced without prior warning that it was ending its relationship with its Beijing Center, effective mid-2019. The center had seen fewer domestic enrollments — from 41 in 2015 to 29 in 2018 — but China remained a popular place for Loyola students to study abroad. (Loyola retained its two other international campuses, in Vietnam and Rome.)

John Pincince, a senior lecturer in history and director of the Asian studies program at Loyola, said he was unavailable for an interview. But he confirmed, as reported in the AAUP study, that he only heard about the Beijing Center closure by reading the student newspaper.

Loyola’s Chicago Center, which facilitated international student exchanges with 19 partner universities, was dissolved around the same time, according to the report. Four of its 19 programs were active and eventually canceled.

Since the cuts were made, according to the report, Loyola has attracted fewer international student enrollments than peer institutions. While seven of the 10 universities included in the report saw significant increases in international enrollment in 2019, “Loyola stands alone with a double-digit, 12.6 percent drop,” it says.

The report notes that Loyola’s vice provost for global programs resigned in 2018, as did the executive director of international programs, in 2019. Neither position has been filled.

Source: Loyola AAUP Chapter, citing 2019 “Open Doors” report figures.

Why has Loyola been unable to attract significant numbers of international students when other universities have, the report asks? Are “our leaders aware of our poor performance?” As domestic university enrollments are projected to decline, why wouldn’t the university invest in international students, as others have done?

As for the language learning program, the report says it provided English instruction, tutoring and assistance for thousands of students over its 40-year history. It was self-supporting financially and came to serve as an important tool for international student recruitment, as many of the students in intensive, English-only programs — such as those who were working to pass the English language proficiency test, the TOEFL — later enrolled as full-time college students. Other students at the center had conditional acceptance to various Loyola academic programs but needed to achieve greater fluency; nearly all of these students ended up studying at Loyola. The center offered tutoring, pronunciation help for faculty members, and even some pre-collegiate programs that were recruiting opportunities in their own right.

Shuffleton said the Test of English as a Foreign Language point is key, in that some Loyola applicants might be “excellent students but fall short” of the cutoff score in English. So “some promising engineering student, or philosopher, or aspiring school leader might get a lot out of Loyola and contribute a lot in turn — but need some extra help with English language in order to succeed in his or her courses.”

Saying she’d had such students eventually turn up in her own classes, Shuffleton said contributions of international students were “invaluable.” Still, the specialized instruction they needed in English was something that even the best professors of other subjects weren’t qualified to provide.

A Success Story

In 1996, the program had just 10 students and two teachers. Over time, it grew to five full-time and several part-time instructors, consistently covering its operational expenses and bringing additional profits to the university. Direct “profits” for Loyola’s English language learning center reached at least $825,000 in 2015, according to the report, with dramatic surges in students from Saudi Arabia and Brazil due to state-sponsored study abroad programs in those countries.

While the Brazilian and Saudi numbers have leveled off in recent years due to in-country changes, English language programs at Loyola and nationwide are returning to a “new normal” at pre-2011 levels, the report says. Program enrollment peaked at 377, or 225 unique students, in 2015, while the unique student number was 138 in 2018. Even then, the program generated a direct profit for the unit of almost $200,000, according to the report.

Source: Loyola AAUP

The program performed at that level even without a leader between the termination of the previous associate director in early 2018 and the hiring of the current associate director, Ryan Nowack, at the end of that year. It was still covering costs, but Nowack was charged with increasing enrollment, increasing profits, building institutional partnerships and aligning the program with global trends.

Nowack declined an interview request. As his work was presumably under way, just several months later, the university stunned program staff by announcing that English language learning would cease operations as of June. No teach-out plan for students was provided, and neither the University Senate nor the Faculty Council or other international program staff were notified ahead of time, to AAUP’s knowledge.

In response, in May, the Senate passed a resolution calling for the administration to cancel the closure of the program pending a re-evaluation of its consequences, release all relevant documentation and review the process by which the decision was made.

The program was kept open. Even so, the administration’s actions have “decimated” the program. It’s down to the one employee, who according to the report, may not recruit recruit or accept intensive English students. The only students the center is authorized to teach are those few who have been conditionally accepted to other academic programs.

Internally, the administration has cited a cost savings of $750,000 per year due to the closure, the report says. “We do not understand where this figure comes from. The interim provost’s own data show that total direct costs for the [program] in 2017-2019 were only ~$430,000 per year.”

The AAUP points out, again, that the losses are probably greater when accounting for the lost international student recruitment opportunities. “We estimate that in closing the [program] the administration has, at minimum, lost several million dollars annually for the university.”

Looking Ahead

Acknowledging the complexity of navigating international enrollments, the AAUP calls on the institution to follow association procedures and Loyola’s own stated governance policies. Changes to academic programs require a review and recommendations by the University Senate, for example.

To that point, the AAUP chapter recommends filling various administrative vacancies in global education. Restoring the English program to its former scope also “would offer Loyola the chance to regain its international reach and shore up its bottom line in the process. Indeed, were Loyola to grow its international student body to the average level of peer Catholic and Jesuit Universities — an average of 12.5 percent — it would generate millions, possibly tens of millions, of dollars each year from this added tuition.”

Of course, the report says, the AAUP’s role is not to make policy, which it calls the “prerogative and responsibility of administrators and co-governance bodies such as the University Senate and Faculty Council.”

Those groups, however, “can only live up to this responsibility if they have a transparent, rigorous, and accurate financial picture of the sort neither provided by the administration nor within our capacity to develop.”

The groups urges its Loyola’s new provost “to take up this challenge with the haste and urgency that the importance of international outreach to our Catholic, Jesuit mission demand[s].”

The university said in a statement that it disagreed with the premise of the report, including its assertion that there has been a “series of shocks that has seriously undermined the university’s ability not only to fulfill its mission, but also to claim credibility as an excellent national university.”

Loyola is working to expand the university’s global initiatives, a spokesperson said.

Kaufman, in his statement, said that Loyola would like to respond in a “thorough and accurate manner to address the many inaccuracies and misconceptions made in this report to ensure that an accurate vision of Loyola’s global enterprise and strategy is represented.”

Benjamin Johnson, an associate professor of history at Loyola and president of the AAUP chapter there, said that beyond having immediate concerns about international students and programs, faculty members want a return to normal, academic governance, “where if you’re going to make big, consequential decisions, they go through a process and faculty bodies are involved in assessing them.”

Professors also have financial worries, he said, “as we were told that all these dramatic measures were necessary to finance big debt payments. But they seem to have cost the school a substantial amount of money.”

“We want to be a smart, financially savvy school.”