New research says relatively simple interventions are effective in addressing faculty workload imbalances and inequities

Author: Colleen Flaherty

Go to Source

Faculty work is not one-size-fits-all. Even within departments and among professors of the same rank, some faculty members tend to do more work than others — or at least more of certain kinds of work. Women tend to do more service work than men, and underrepresented minorities tend to do more mentoring of the students of color who look to them as role models, for example.

Ideally, it all balances out. But many times it doesn’t, especially because mentoring, service and other tasks are typically underrewarded within academe. And that can cause major problems, such as lost morale and lost research time — and the professional consequences that come with them, up to faculty attrition.

If the consequences of faculty workload inequity are grave, there have been few to no widespread interventions to address it. But a promising new study suggests that change is possible.

The study, which is ongoing, involves 17 departments and an additional 13 control departments across different institution types in Maryland, North Carolina and Massachusetts. For 18 months, researchers helped put in place four interventions against workload imbalances: increasing faculty awareness of implicit bias, making data on work activity transparent, sharing organizational practices to encourage equity and providing individual professional development to help faculty members align their time and priorities. Those latter two factors are what lead author KerryAnn O’Meara, professor of higher education and an associate dean at the University of Maryland at College Park (and an occasional opinion columnist for Inside Higher Ed), recently called “allies of work equity.”

More specifically, the interventions included a workshop on how implicit bias can shape faculty workload allocation and guidance on how to collect and share transparent annual faculty work activity data in a “dashboard.” Researchers also showed departments how the dashboard could identify equity issues and provided a variety of sample organizational practices to address them. They helped programs develop an action plan by adopting the organizational practices that they thought would address the issues revealed in their data. And faculty members took part in an optional four-week individual time management and planning webinar. Teams of three to five professors within each department were responsible for putting the interventions in place. But all materials were offered to all participating department members.

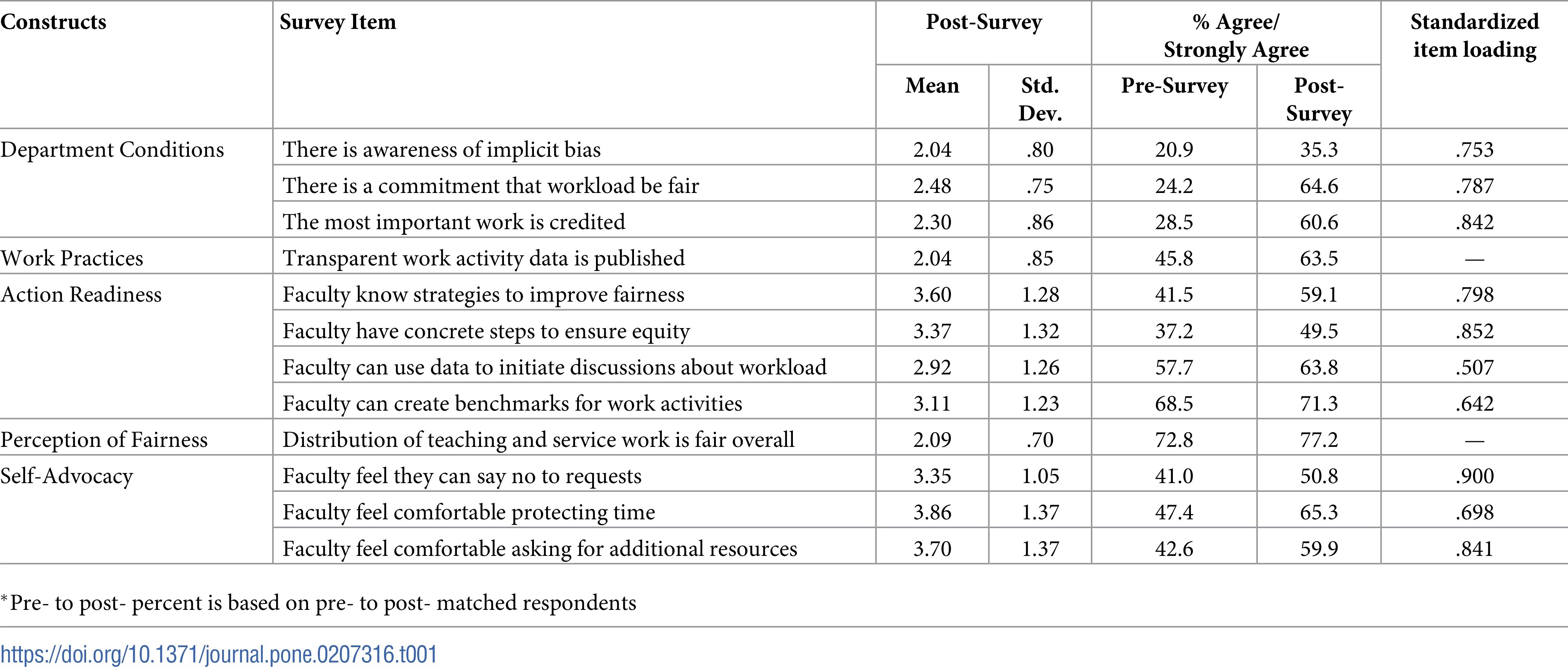

Comparing outcomes from participating departments and the controls, the researchers found that the interventions made a positive difference on the faculty experience of workload fairness across demographic groups. Pre- and postintervention surveys of faculty members in participating departments also reveal, for example, that professors now feel more aware of implicit bias and are more comfortable protecting their time, saying no to requests and asking for more resources.

“We aimed to improve: transparency in what faculty are doing, accountability, clarity in roles and expectations, and flexibility to acknowledge different contexts,” reads the first phase of the study, which was published recently in PLOS ONE. Attributing their results to a “spillover effect” from the workload dashboard in particular, the authors wrote that transparency “increases sense of accountability and trust between members and leaders, facilitates perceptions of procedural and distributive justice, and leads to greater organizational commitment. Departments that routinely make data on faculty activities accessible are likely to promote perceptions that workloads are transparent and fair.”

In other words, the study says, “as participants saw members of their department were serious about improving equity in division of labor, and recognized their workload relative to others due to the transparent dashboards, they felt greater permission to likewise self-advocate and take steps to ensure their own workload was fair.”

O’Meara said that national surveys, interviews and focus groups have for decades shown that faculty are “dissatisfied with workload” and, in some cases, even leave their institutions because of it. That’s especially true for women and underrepresented minorities, “who often do a greater share of mentoring, advising and campus service work,” she said.

Sometimes the problem is that the amount of work in certain areas, such as campus service, diversity work or advising, isn’t shared, O’Meara explained. In other cases, “the process used to assign more coveted roles is not transparent,” she said, and sometimes the equity issue is that some work is not visible or credited. There’s additional talk about faculty “free riders.”

Still, there’s been no “laser-like” cross-department or cross-campus focus on workload equity, as there has been on issues such as inclusive hiring or leadership development, O’Meara said. Workload has rather been “embedded in attempts to improve department climates and into mentoring rubrics and department chair training.”

Kiernan Mathews, director of the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education, is among those who have praised the study’s methodology and relevance. Asked why it’s valuable, Mathews said the workload problem has “grown only more acute since COACHE began studying faculty.” Why? For presidents and provosts who want their institutions to move in a new direction, he said, “the levers ultimately come down to money and time — and nobody seems to have any money.”

More than that, Mathews said the research takes an equity approach — one that’s much needed in academe, where inequities abound, especially in “foggily” negotiated workload assignments (to borrow O’Meara’s often employed term). The study is large-scale, long-term and experimental, he said, testing four interventions instead of one. Mathews also praised the publishing journal, saying it’s “high-impact” and outside the “usual higher ed suspects,” lending “authority to an area of study — faculty development — that doesn’t typically get this kind of treatment.”

O’Meara and her team plan to collect more data going forward, to test their hypothesis that the interventions will have differing effects. In the fifth and final year of their project, they hope to share resources and materials created for the project with other institutions so that professors have better work experiences — both in “perception and reality,” O’Meara said.

Mathews said he’s looking forward to the rest of the data.

“I can’t wait to see what’s still to come from this study.”