Russia: The Unlikely Place for a Proletarian Revolution

Author: gunjan.sogani

Go to Source

By Vejas Liulevicius, Ph.D., University of Tennessee, Knoxville

According to Karl Marx, proletarian revolutions could happen only in industrialized and developed countries, and so Russia seemed to be the most unlikely place for such a revolution. Then, what happened in 1905? Whose trust was broken forever?

(Image: Peyker/Shutterstock)

Karl Marx envisaged that only an educated and wealthier population in developed countries would be ready to participate in a proletarian revolution. He believed that such a population would respond better to the need for changes in society. European countries such as Germany, Britain, and France were industrialized and seemed to be key models of success, growth, and cohesive nationalism. In fact, Germany seemed to be a promising prospect for Marxism to flourish due to the presence of an organized and disciplined party set-up and constantly growing memberships.

In contrast, Russia was still a backward country that grappled with its feudal systems. It had a huge population of about 164 million, comprising of around 200 large and small ethnic groups. Geographically, the Russian Empire extended over a vast area from Finland across Siberia to the Pacific. It was so large that it had 11 different time zones and covered a fifth of the world’s dry land. Further, it was an agrarian country with over 80 percent of its population living in rural Russia. Industrialization was just beginning in some of the urban centers like St. Petersburg, Moscow, Warsaw, and Lvov. Yet, despite all these shortcomings, Russia became the breeding ground for many a political revolution.

Reasons that Led to the Russian Revolution

Miserable lives of peasants. Though the peasants in Russia had been freed from serfdom, they had to work to pay the cost of their liberation back to the state. These peasants yet hoped that someday the Tsar might correct the abuses of the society and favor them. On the contrary, the economic misery of the peasants only increased during the famine of 1891 due to failed harvests and mass hunger. Further, epidemics including cholera and typhus killed half a million of the already weakened rural population. Even under such dire circumstances, the state’s response continued to be ineffective and unsympathetic.

Conservative and authoritarian political system. The Romanov dynasty of Tsars ruled Russia for over 300 years and thought themselves to be divinely ordained, a concept that was outdated in Western Europe. In addition, the aristocracy in Russia, which continued to enjoy the revenues from estates across the Empire, was completely disconnected with the social and economic hardships faced by the peasants and workers

Brutalities of the police state. The Tsarist forces spread their tentacles across Europe, be it to support the Austrian Habsburgs suppress the Hungarian rebellion, or to use Cossack cavalry forces to brandish the famous whip, the nagaika, against protestors. Not surprisingly, the Empire earned nicknames such as “Policeman of Europe’ and “Prison House of Nations”. The Tsar’s secret police stifled liberal movements, searched out every opposition, and spied on revolutionaries in exile across Russia. The Russian regime also encouraged violence and discrimination against the Jewish minority. These anti-Jewish pogroms led to waves of Jewish immigration.

Epidemic alcoholism. The Russian state exploited vodka sales for fiscal purposes. Vodka sales accounted for about 40 percent of the state revenue and were the single largest source of income for the government. Thus, the state was largely responsible for the epidemic alcoholism prevalent among the poor.

To summarize, the state was marked by poverty, repression, and underdevelopment, all of which provided a combustible mix for a revolution to erupt. And among the intellectuals, this state of affairs often led to despair.

Learn more about the nobility, the Tsar, and the peasant.

‘Intelligentsia’ in the Russian Society

One of the most influential and diverse groups in Russian society was a group of educated people called the ‘intelligentsia’. Interestingly, from the 1860s to the outbreak of the First World War, when university enrollments grew by over 13 times, this group also grew by leaps and bounds. These publicly active Russian intellectuals criticized and opposed the injustice and inequalities practiced by the state. Subsequently, the uncompromising state exercised heavy-handedness and persecuted these reformers. Historians feel that their deep sense of obligation toward society, coupled with inaction from the state often led these frustrated intelligentsia to turn into revolutionaries and terrorists.

This is a transcript from the video series The Rise of Communism: From Marx to Lenin. Watch it now, on The Great Courses Plus.

The Unexpected Russian Revolution of 1905

At the beginning of the 20th century, multiple groups were planning the Russian revolution from different perspectives. But, when the revolution actually broke out in 1905, it took these groups completely by surprise.

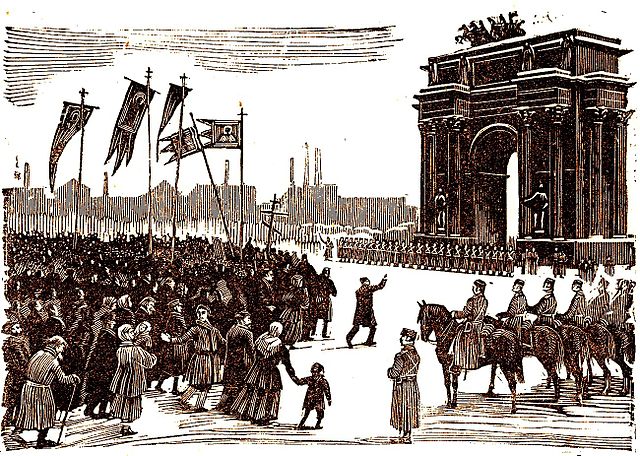

The Russian revolution of 1905 came about as a result of both political and social discontent across the vast expanses of the Russian Empire. Internal discontent was further fueled by the humiliating defeat of Russia at the hands of imperialist Japan. But it was on the ‘Bloody Sunday’ that the people’s trust in the Tsar was broken forever.

The entire Russian Empire erupted in disorder and collapsed internally. Peasants sacked manor houses, burned land records, and attacked landlords, destroying nearly 3,000 estates. Nearly 75 percent of the factory workers went on strike, while railroad workers shut down the communication network. A mutiny took place on the battleship Potemkin in the Black Sea as soldiers took control hoisting the red revolutionary flags. The revolt also spread to non-Russian expanses of the Empire such as Poland, Lithuania, and Finland.

As a result of this revolution, workers and soldiers established their own councils called ‘soviets’, meaning councils. These grassroots councils represented the legitimate political authority. Meanwhile, in St. Petersburg, a central soviet or council of councils was established under the Social Democrat Leon Trotsky. However, the fundamental character of the 1905 revolution remained the same—‘it was not steered by any one leader’.

The scale of this revolt finally forced Tsar Nicholas II to declare reforms in the ‘October Manifesto’. He promised a few reforms, including the establishment of a parliament, the Duma, with limited powers. These limited reforms satisfied some moderate revolutionaries and weakened the opposition of the St. Petersburg soviet. It also helped the government arrest revolutionaries like Trotsky. However, the revolution of 1905 set the stage for the successful revolution of 1917, which was led by Lenin. Later, Lenin described the revolution of 1905 as an essential ‘dress rehearsal’ for the revolution of 1917.

Learn more about the revolutionary ideas of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

Common Questions about the Proletarian Revolution

A proletarian revolution is a social revolution where the working class tries to depose the bourgeoisie. The Marxists believed that proletarian revolutions were likely to happen in developed and industrialized countries.

The Russian intelligentsia was a group of influential educated people in Russian society who shared a common identity due to their education and professional training. They criticized the Tsarist regime in Russia for the injustices meted out to its citizens.

On January 9, 1905, the Russian Imperial troops fired at a group of 10,000 unarmed, peaceful protesters. This incident, known as ‘Bloody Sunday’, broke the people’s trust in the Tsar forever and triggered the revolution of 1905.