The pandemic has worsened equity gaps in higher education and work

Author: Paul Fain

Go to Source

Even before the pandemic, higher education faced growing scrutiny about its role in contributing to severe societal equity gaps that afflict black and Latino Americans, as well as Native Americans and other historically underserved groups.

But that pressure is certain to increase amid what Richard V. Reeves, a writer and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, calls an extraordinary “collision of crises” that has further exposed multiple inequities and inequalities.

Those widening chasms include the pandemic’s impact on the labor market. Black and Latino workers are more likely to have lost their jobs, while white and wealthier Americans are much more likely to be able to work from home and to not be deemed essential, front-line workers, who are more likely to be exposed to the virus, said Reeves during a webcast hosted by Jobs for the Future last week.

Likewise, the severe wealth gap means people of color are much less able to cope with the loss of a job or wages. And inequity in society has contributed to higher COVID-19 mortality rates among black and Latino Americans, said Reeves, due to poverty’s relative impact on their health and the enhanced risks of coming down with COVID-19 on the job or on public transportation.

“The whole U.S. political economy was like a giant pre-existing condition,” Reeves said. “And COVID came along and exposed it all.”

None of the pandemic’s disproportionate impacts on postsecondary education and training should be a surprise, said a wide range of experts. But the crises have accelerated those problems while also worsening them.

“The toll of this pandemic is, in a word, devastating,” John King Jr., president and CEO of the Education Trust and a former U.S. secretary of education during the Obama administration, said during a call with reporters in late May. “It’s eroding students’ academic success, their emotional well-being and their personal finances.”

That impact has been felt most profoundly by students of color. And some initial data suggest that lower-income students and those from minority groups may leave higher education, perhaps permanently.

Lorelle Espinosa, vice president for research at the American Council on Education, cited growing evidence that underserved student groups may be falling away from higher education amid the pandemic, recession and national racial crisis. And Espinosa said students who stick around may take on more debt.

“I’m really worried that those students won’t come back at all, or they might come back much later,” she said. “Even if they stay, the educational experience may be really disruptive and misaligned to their learning needs.”

Disproportionate Impacts

When colleges around the country closed campuses and pivoted to online learning in mid-March, leadership at the Strada Education Network felt that the country was on “wartime footing,” said Dave Clayton, senior vice president of the nonprofit corporation’s Center for Consumer Insights.

Strada quickly decided to shift its polling and survey efforts to monitor the pandemic’s impact on American’s lives, work and needs for education and training.

The former student loan guarantee agency USA Funds became Strada in 2017 after a multiyear restructuring. The group features an unusually arrayed network of affiliates focused on connections between education and work.

Strada for years had teamed up with Gallup on a large polling data set of consumer perspectives on the value of education to people’s careers and lives. By late March, however, as unprecedented disruptions roiled higher education and the economy, Strada’s Consumer Insights had revamped its survey approach to create the Public Viewpoint poll, which focuses on COVID-19 and its impact on education and work.

(Note: Inside Higher Ed and Strada Education Network partner on Public Viewpoint. Strada provides funding to Inside Higher Ed to support its coverage of the polling data and related workforce issues. Inside Higher Ed maintains editorial independence and full discretion over its coverage.)

The nationally representative survey was in the field by March 25 and received more than 10,000 responses by May 28. Strada asked respondents about their job security, income and anxiety. The poll, which began on a weekly basis and has since moved to every other week, also includes questions about future education plans.

“Immediately it was clear that leaders who were going to be serving people needed more information,” Clayton said. “Americans need their leaders to understand their circumstances.”

The survey quickly identified areas where the pandemic has exacerbated inequity in work and postsecondary education.

Results released on June 10, for example, found that roughly one-quarter of black Americans (23 percent) and Latinos (24 percent) have been laid off, higher shares than white (15 percent) and Asian Americans (13 percent). Black and Latino respondents also were likelier to report starting new full- or part-time jobs in the past month, Strada found.

Most respondents are anxious about their employment, with more than half reporting worries about losing their job during each of the 10 weeks of polling — a high of 68 percent said so in results released April 1. Given the nation’s wealth gap, with research showing that an unexpected cost of $500 or less can severely derail large percentages of black and Latino families, reduced hours or a layoff can be catastrophic.

“How are people going to manage through this?” Clayton said.

The survey includes some forward-looking elements, with an eye toward changing employment opportunities (and barriers). It looks at the integration of postsecondary education and training with the job market, to help state policy makers and workforce development officials focus on “preparation to get back to work,” said Clayton.

That approach is both useful and, to some degree, uplifting, said Jane Oates, president of WorkingNation and a former official in the U.S. Department of Labor during the Obama administration.

Oates said that’s because colleges and employers can draw from the data to help design pathways for low-income people back into the workforce during a recovery, ideally with credentials that lead to both a well-paying job and, eventually, to a college degree.

“How do we make sure that this temporary shift doesn’t become a brick wall?” she said.

Exodus of Low-Income Students?

In a more immediate sense, with a recovery still likely months or years away, the Strada data build on other indicators that students, particularly those from low-income and minority backgrounds, may ditch higher education.

Roughly three-quarters of undergraduate students (77 percent) who responded to a recent poll from Education Trust and the Global Strategy Group said they were worried about being able to stay on track and graduate. Those shares were higher among black (84 percent) and Latino (81 percent) students.

“Many may soon not be students at all. They’re considering leaving school,” said King, in part due to the heavy burdens of stress they’re shouldering.

The survey also found that 80 percent of students are very concerned about not being able to get the skills or work experience they need to get a job after completing college — a number that rose to 85 percent among students of color.

Those numbers reinforce a federal data analysis from the National College Attainment Network. The group is tracking college student renewals of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, which it says correlate strongly with college enrollment and so far are down over all by 3.2 percent compared to last year.

NCAN found steep declines in renewals beginning in mid-March. Those numbers improved in May, but not enough to cover earlier declines, particularly among low-income students.

Through May 31, the group found a 7.2 percent decline in renewals among returning college students with annual family incomes of less than $25,000 — a drop-off of roughly 240,000 students.

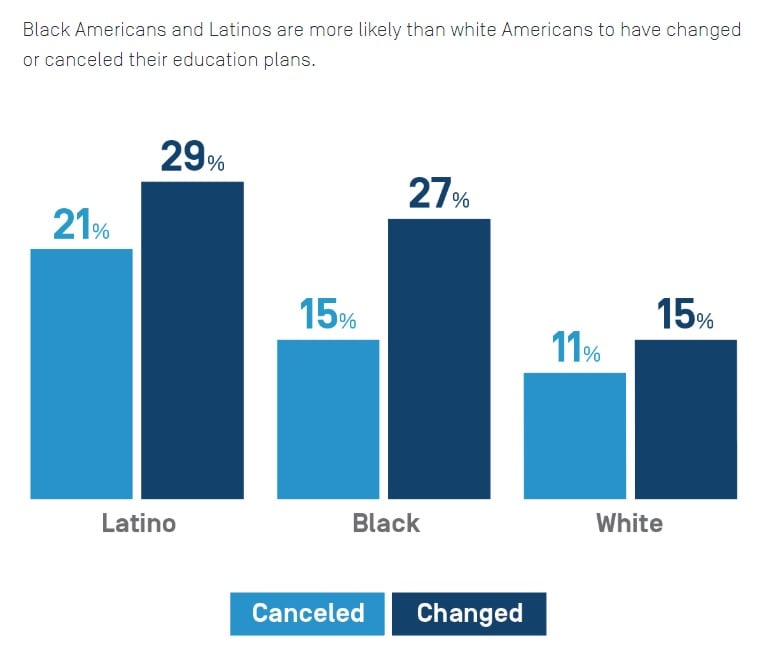

Strada on June 10 released survey results on whether respondents had canceled or changed their education plans. Higher percentages of Latino (50 percent) and black (42 percent) Americans reported disrupted plans than did white (26 percent) respondents.

Kim Cook, NCAN’s executive director, said anxiety and uncertainty are likely drivers of these trends.

“Any uncertainty can really rattle you,” she said, “particularly if you’re the first in your family to go to college.”

Scrutiny for Employers and Colleges

Doubts among lower-income Americans about investing in a college education are understandable, particularly during this time of crisis, said Aimée Eubanks Davis, founder and CEO of Braven, which works with San José State University and three other colleges and universities around the country to help underrepresented students transition from college to jobs.

“Before COVID you already had a big recession happening for certain groups of students,” said Davis, pointing to data that show a much smaller wage bump for bachelor’s degree holders who come from lower-income backgrounds compared to their wealthier peers.

Getting a well-paying job often depends on skills that too many underserved student groups don’t get while attending college, Davis said. “Higher-income kids are getting that from their parents and their peer groups.”

Those challenges likely won’t ease during a prolonged recession, she said, where the cash-strapped public colleges that enroll most lower-income students already have career services departments that are stretched too thin to adequately help many students.

Even so, Davis is more optimistic that traditional higher education will change in coming months and years to close equity gaps than she is about employers.

“I get more skeptical in a recession,” she said, adding that a scarcity of jobs makes her worried about companies meaningfully changing how they find more diverse talent. “If there’s not intentionality, these things don’t happen.”

Employers must not go back to business as usual amid the recovery, Jim Shelton, chief investment and impact officer at Blue Meridian Partners, an investment firm focused on economic mobility, said during the Jobs for the Future webcast.

Companies need to “lean as hard as ever” into thinking differently about their talent strategies, said Shelton, who formerly led the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative’s education arm and worked as an official at the Education Department. “We’ve got to make those things a part of the way that companies see their role in creating a new future and an economy that can work for everyone.”

The Strada survey can help connect the dots with actionable data for both employers and education providers, said Maria Flynn, JFF’s president and CEO.

“What are the actions that can be taken coming out of this that keep the equity frame in the center?” she said in an interview. “What are those no-regret solutions, regardless of how the recovery comes?”

Trust and Advice

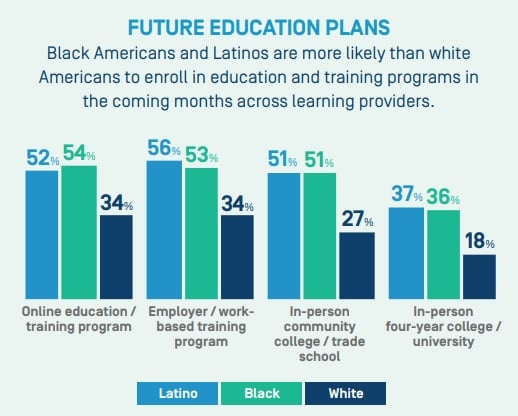

The Strada survey found that black and Latino Americans are particularly likely to say they will enroll in education and training programs in coming months. That could be an opportunity for higher education to make inroads with underserved populations.

However, the poll found that these potential students are more likely to consider nontraditional providers, such as online and employer-based training programs, as well as community college, over an in-person, four-year college or university for that education and training.

Likewise, black Americans rank advice from colleges about education and training options as less valuable than advice from other sources.

Strada found that black respondents put higher education last, after advice from family, the internet and employers. Latino and white respondents said advice from colleges and universities was the second most valuable, after their families.

To better serve these student groups, Espinosa said she is encouraging college leaders to directly take on diversity, equity and inclusion as top priorities. And she said that means taking real action rather than just acknowledging the industry’s shortcomings.

“It’s unfortunate that you have to go through a crisis, often in higher education, to get serious about something,” said Espinosa. “But I see that we have the potential to get serious right now.”