Higher education lobbying has declined, but will that change?

Author: Kery Murakami

Go to Source

A decade ago, Bucknell University was among 700 other higher education institutions and groups that spent about $100 million to hire lobbyists in Washington — many of them hitting up members of Congress for earmarks to pay for things like a new campus lab or building.

But in the years since 2011, when federal lawmakers stopped handing out earmarks to their favorite projects, much has changed in how higher education lobbies.

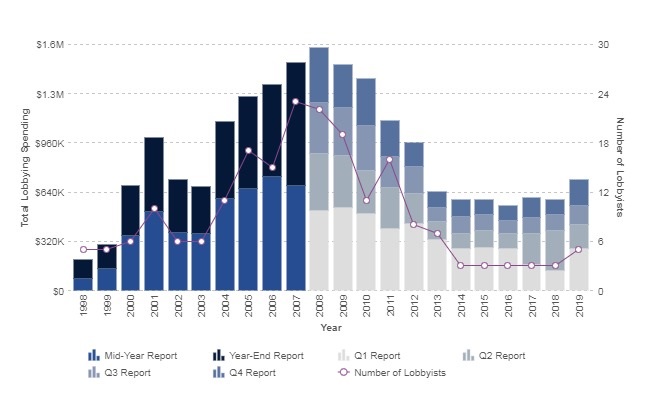

Many smaller and midsize institutions, like Bucknell, have decided to not spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on D.C. lobbyists if they can no longer get a line inserted in the budget for new equipment or a building. The number of higher education institutions and groups hiring lobbyists to influence Congress has dropped by about a fourth between 2010 and 2019, from 683 to 396, according to an Inside Higher Ed analysis of federal lobbying disclosure data.

All told, the industry spent about $74.5 million to lobby Congress in 2019, roughly $22 million less than the $96.4 million it spent in 2010.

Disclosure records also show changes in which institutions are lobbying Congress.

“We noticed a trend where the smaller or midsized schools pulled back from lobbying,” said Leslee Gilbert, vice president of Van Scoyoc Associates, which represents a number of institutions, including the University of New Mexico, University of Utah and University of Toledo.

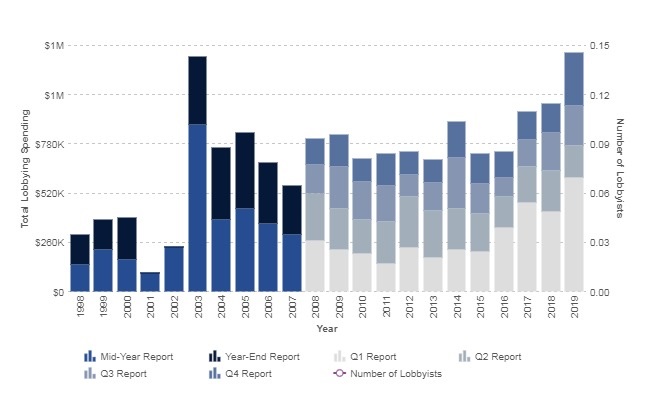

However, some larger research institutions, including the University of California system, have ramped up spending on federal lobbying, a shift Gilbert said has made it harder for smaller colleges to get federal funding.

“In 2010, Congress was still using earmarks in the appropriations process, and a lot of work was devoted to this particular part of advocacy,” said Terry Hartle, the American Council on Education’s senior vice president for government relations and public affairs.

Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives reportedly are considering a return to earmarks, at least on a limited basis, although lobbyists like Hartle and Gilbert are skeptical House Democrats will do it. If that change happens, lobbyists and some institutions say more colleges will go back to hiring D.C. lobbyists.

“It’s logical that if a pool of funds like this again becomes available, organizations will engage firms to assist them in accessing those funds,” David Surgala, Bucknell’s vice president for finance and administration, said in an emailed statement.

Bucking the Trend

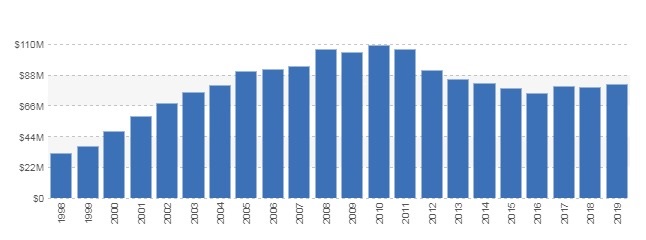

The drop in congressional lobbying by higher education reflects an overall drop in spending on educational lobbying, including K-12, according to data compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics, a D.C.-based group that tracks campaign contribution and lobbying spending.

Inside Higher Ed’s numbers are based on spreadsheets created by the center on education lobbying.

According to the center, $80.9 million was spent last year to lobby on education, down from $109.1 million in 2010. That runs counter to lobbying trends over all. About $3.5 billion was spent on federal lobbying last year, the center said, an amount that didn’t change much from the previous year.

One caveat about the numbers, Hartle said, is that lobbying rules only require the disclosure of spending to influence Congress, not federal agencies like the National Institutes of Health, where higher education lobbying continues to draw federal dollars.

Another factor in the decline, Hartle said, is that not as much is happening in Congress as in 2010, which featured major legislation like the Affordable Care Act, the Dodd-Frank Act regulations on financial institutions and a revamp to the federal guaranteed student loan program.

While lobbying Congress may have dropped off, efforts to influence the U.S. Department of Education and other agencies has continued, if not increased, at a time when agencies consider changes to policies around accreditation and how campuses deal with allegations of sexual assault and harassment.

“The paralysis on Capitol Hill has reduced the amount of legislation that gets enacted, and this reduces the amount of time we spend lobbying,” Hartle said in an email. “But we are probably spending more time interacting with the executive branch now than ever before.”

As for lobbying Congress, institutions like Bucknell, California State University, the State University of New York and the City University of New York have scaled back or stopped entirely.

Bucknell, for instance, spent $120,000 on federal lobbying in 2010. Over the years, “Bucknell has received a few earmarks for capital items — e.g. scientific equipment and maybe some help with facilities projects,” said Mike Ferlazzo, a university spokesman. But it spent $90,000 in 2018 and nothing last year.

“Federal earmarks from legislators are no longer the same as they were in prior years. Our focus has changed from lobbying for earmarks to engaging a firm to help us with grants from places such as the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health and the National Endowment for the Humanities,” the university said in a statement.

According to lobbying data, Cal State, which spent $1.3 million in 2010, spent about half as much ($724,000) last year. SUNY’s spending dropped from $1.8 million to $220,000 during the same period. CUNY spent $30,000 in 2010 but nothing last year.

A SUNY spokeswoman attributed the decline to becoming more efficient and having university staff handle lobbying. Cal State in a statement said, “It does seem likely to us that Congress’s decision to ban earmarks in 2011 has contributed to a decline in lobbying expenditures by institutions of higher education, including the California State University.” But other factors like the recession, greater emphasis on seeking competitive grants and the inability of Congress to reauthorize the Higher Education Act since 2008 contributed as well, the statement said

Return to Earmarks?

For smaller colleges, it’s still possible to get federal dollars from agencies, even though members of Congress representing their area can no longer get a line in the federal budget for a pet project.

However, lobbyists who represent small and medium-size institutions say it has become more difficult for them to get funding. Without earmarks, the action has shifted to getting money from federal agencies, and major universities are also chasing those dollars. The battle for funding “is highly competitive, highly,” said one lobbyist who represents smaller institutions.

That’s unfair to students who attend smaller institutions, the lobbyist said. “Most kids go to college within 50 miles of where they live. All students in the U.S. should have access to really quality experiences and great scientific resources.”

The lobbyist complained, “The big ones have gotten bigger.”

The University of California, for instance, spent $1.3 million in 2019, nearly twice the $700,000 it spent in 2010.

Stett Holbrook, a UC spokesman, said lobbying expenditures have risen because of a number of factors, including “issues before Congress and the administration, and the amount of time associations spend on lobbying done on members’ behalf.” He also said in an email that “UC has not relied on directed funding or so-called earmarks. As such, our lobbying efforts have not been tied to that process. We strongly support the peer-reviewed, competitive grants process through which our researchers have achieved great success.”

A lobbyist who represents research universities said many of those institutions ramped up their presence in Washington after the end of earmarks in order to build deeper relationships with agencies that fund research. Another lobbyist said institutions that conduct work on detecting viruses are talking to agencies as the government deals with the coronavirus outbreak.

As first reported by Politico in January, House Democrats are considering bringing back earmarks by allowing the funding of a controlled number of lawmakers’ local projects from limited pots of federal cash. New restrictions would bar money from going to for-profit businesses but would allow nonprofit colleges and universities to again be able to receive earmarks.

While the practice has been derided, some said there would be advantages in bringing back earmarks.

Influential interests can still seek money even without earmarks, said Jason Grumet, president of the Bipartisan Policy Center. “But while they used to do it overtly, now they’re calling up the heads of agencies behind the scenes,” he said. “The irony is that in the interests of greater transparency, we’ve driven discussions further underground.”

In addition, he argued that restoring earmarks could make it easier for lawmakers to make tough decisions on a national scale, such as getting the national deficit under control. “We want members of Congress to have the courage to make decisions that will not be received well back home,” he said. “To do that, they’re going to need some political capital.”

However, lobbyists are also skeptical Congress will take the risk of being seen as bringing back what’s been derided as wasteful pork during an election year.

The House under Republican and Democratic leadership in the last few years has considered bringing back earmarks, Grumet noted. “But in the 11th hour, they’ve gotten cold feet,” he said. “Earmarks are one of those things that have been caricatured.”