How Schools Can Use Life Transitions To Help Students Feel They Belong

Author: Katrina Schwartz

Go to Source

Transitions are important in the lives of young people. Moving from elementary school to middle school, or from middle school to high school, represents a big change in academic expectations, schedules, and social lives. These powerful moments of transition are also times when schools can focus on building a sense of belonging among incoming students that could make a lasting impact on their ability to achieve academically. When students feel like they belong to a community, that they are in the right place, they are more likely to succeed academically. And they’re more likely to stay in school.

Universities know this research. That’s why the first week at many colleges is full of bonding activities, chances to make social connections, and intentional planning to heighten the emotional power of an already exhilarating moment in a young person’s life.

In their book The Power of Moments, Chip and Dan Heath write:

“What’s indisputable is that when we assess our experiences, we don’t average our minute-by-minute sensations. Rather, we tend to remember flagship moments: the peaks, the pits, and the transitions.”

The Heaths argue that leaders can learn to spot these powerful moments and plan to heighten their memorableness by shaping them so participants feel they’ve gained new insights, and feel more connected and proud of themselves and their community.

Chris De La Cruz knew all this research from working with CUNY Start, a program designed to help incoming community college students who had failed the subject area entrance exams. He knew that when white students struggle in college they assume it is because they don’t know enough, but when students of color struggle they assume there is something wrong with them. He knew it was important those students feel that they belong in college, that they were valued in the community.

So when De La Cruz started working at South Bronx Community Charter, a high school in New York City, he thought they should use this research to help their freshmen transition to high school. The school was designed to change the outcomes for the young black men and women in the neighborhood. Instruction is entirely project-based, the commitment to restorative discipline practices is extreme, and relationships are at the core of the model. It always had a summer orientation program, what they call Summer Bridge, but it struggled to meet two competing demands: foster a community and introduce students to project-based learning. In the summer before the school’s third year, De La Cruz decided to try focusing purely on belonging for a better experience.

On the first day, students were placed in small groups with a learning coach. These groups helped students get to know each other and open up in a smaller setting, like an advisory. A learning coach at South Bronx Community Charter is not a credentialed teacher, but rather someone skilled in youth development. Often these folks have experience leading after-school programs or working in the community. During the school year, they co-teach with credentialed teachers, sharing their expertise on relationship building and how to make topics engaging for young people. They also teach some elective classes and lead the school’s advisory curriculum.

De La Cruz subscribes to the Brené Brown definition of belonging. She says: “True belonging only happens when we present our authentic, imperfect selves to the world.” He knew from experience that at the start of high school most students are primarily worried about what they’re going to wear and how they’ll fit in. After going through Summer Bridge, he wanted them to know school is a place where they can share their authentic selves and be celebrated.

The first activity called on students to talk about a happy memory, something that makes them angry, and something or someone that inspires them with their Summer Bridge small groups. No one was forced to share, but many did, following the example of the learning coaches who modeled being vulnerable and respectful.

“I was shocked at the amount they opened up,” De La Cruz said. “And of course there were some students who were resistant. Sometimes you get students who are angry resistant, but it was more like a quiet resistance.”

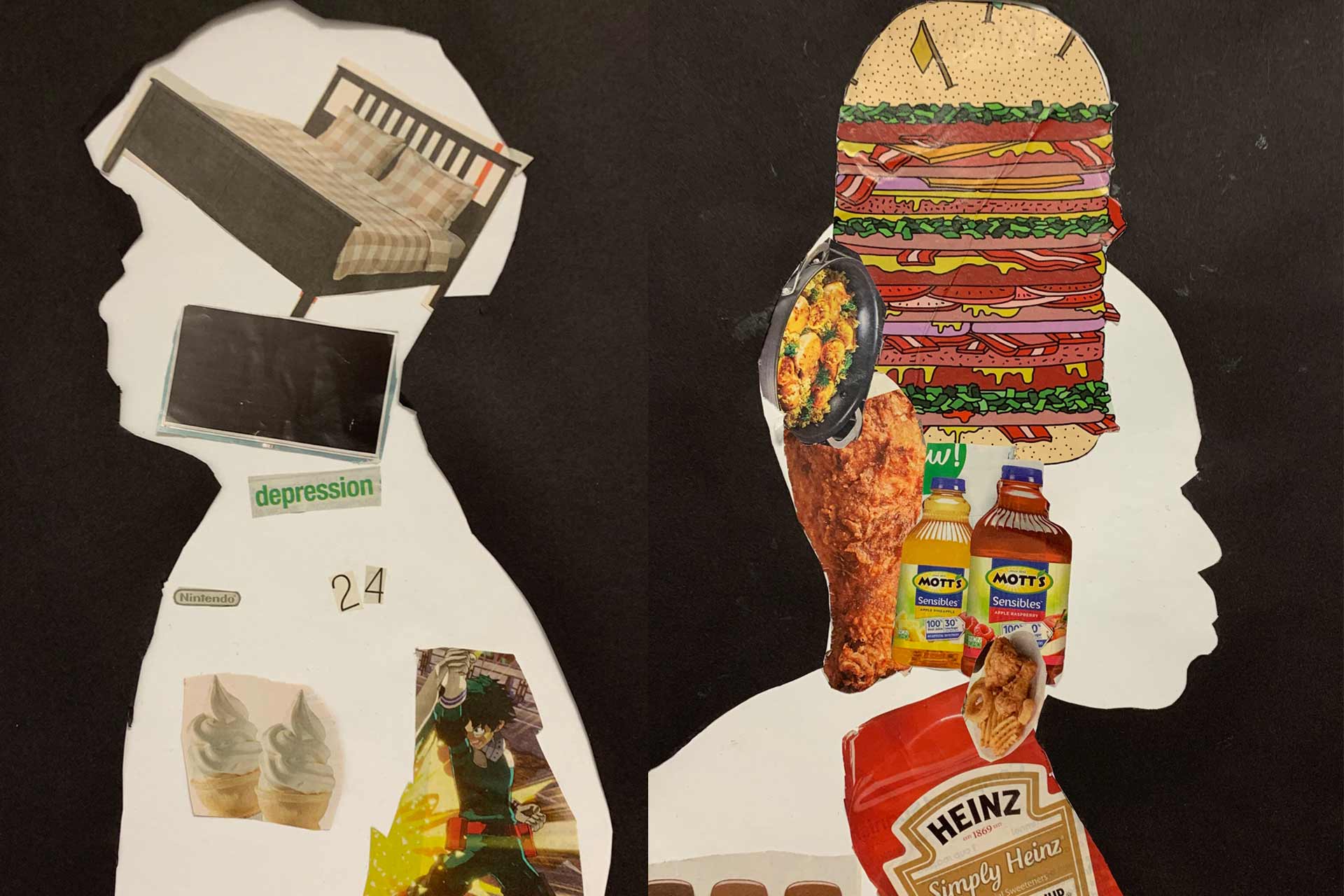

Leaders also introduced students to a self-portrait activity that students worked on throughout the week. They drew outlines of their profiles and filled them in with images and words they felt represented who they are as people.

On the second day, leaders took the incoming ninth-graders out of the city to a ropes course where they worked together in groups to overcome challenges. For many students this was a favorite moment of the week. Everyone was out of their comfort zone and their neighborhood, playing together.

“It was some challenges, but as a team we seemed to overcome them,” said freshman Rhaming Williams.

Day 3 activities assumed some trust had been built by this point. In the same small groups, students wrote letters to themselves from the perspective of a caregiver (mom/dad/grandparent), saying what they’d like to hear from that person. They shared parts of these letters with the group.

“I was hesitant because I didn’t really know these people,” said freshman Hailey Miranda about sharing personal things with the group. But ultimately she decided she felt safe because of the vulnerability her group leader modeled. “She was really opening and she was helping us, even though she didn’t really know us,” Miranda said.

Adult authenticity and vulnerability is an important part of creating the space for this type of community-building work. De La Cruz acknowledges it can be a tricky balance to strike for teachers. He and his staff did the Summer Bridge activities together before leading students in them, so they had the opportunity to feel out the edges of their own experiences.

“You want to share a scar, not a wound,” De La Cruz said. “You want to share something, but something you’ve got a handle on in some way.” When adult mentors share like this with students they demonstrate their trust in them, but don’t inadvertently lean on students for support in an inappropriate way.

The intention behind Day 4 was to connect students to the broader freshmen class community beyond their small groups, and to recognize some of the similarities in experiences they all face. In the morning, they played a game called “Cross the Line,” in which students cross the line if the statement applies to them. The statements started out light, but became heavier, including topics like bullying or experiencing trauma. Again, honesty and modeling from leaders helped students feel confident to bravely share.

On the afternoon of the fourth day, the school held a graduation ceremony, inviting students’ families to be part of the transition into high school. Students hung their finished self-portraits on the wall, and families did a gallery walk through them. Learning coaches had also reached out to parents ahead of time, asking them to write an artist bio of their student highlighting their good qualities. Reading these was an emotional experience for many students.

“My family is big so we don’t have that one-on-one time with our parents that much,” said Rhaming Williams. He said he rarely gets written letters, so it felt extra special. “Reading the letter, being able to feel emotions from my parents, was amazing.”

Another student, Marilyn Valentin, said “it was enlightening” to get that letter. “It was a good experience. I felt great to read that.”

Students also discovered on the last day of Summer Bridge that the small groups they’d spent all week cultivating would be their advisory groups all year. They’d be entering the first day of school with solid friendships already formed. It took some of the pressure off.

“Everybody in this group ended up being really close friends and we share our feelings and thoughts,” Valentin said. She’s learned that when she’s hurt by the actions of a peer, she can go to them and talk about it. She gets support from her advisory group when these issues come up, something she never felt in middle school. There, everyone felt fake, even when they were apologizing. “Before I didn’t know how to handle things like that and it would actually affect me a lot, but now I can handle those things and talk to people more,” she said.

CONTINUING INTO THE SCHOOL YEAR

Treating the transition to high school with an emphasis on fostering a sense of belonging has served the school well. The emotional foundation of their advisory groups — what they call Core groups — has allowed students to adapt to learning through projects. Knowing their teachers and learning coaches care about who they are as people has allowed students to be more vulnerable in academic settings as well. Many students at South Bronx Community Charter start high school behind grade level, but teachers have the attitude that it’s not the kids’ fault when that happens. As teachers they see it as their job to boost students’ skills.

The co-teaching model has also allowed the school to benefit from the strengths of every staff member in the building. Teachers are learning ways to build relationships with students, engagement tactics, and how to be effective advisers from learning coaches. On the flip side, learning coaches are learning strong teaching techniques from teachers, often moving to get their own credentials with a small stipend from the school. And since many of the learning coaches are people of color, this model has the added benefit of making sure students have mentors that look like them in school, while helping people up a career ladder toward credentialed teaching.

“Within the communities we are serving there are a tremendous number of talented people working with youth in effective ways,” said John Clemente, executive director and co-founder of South Bronx Community Charter School. “We saw there’s a need if we can bring those folks into the classroom and we can offer them a career pathway, that’s going to be very appealing for them, and we think it’s going to be really effective for our young people.”

Clemente participated in a New York Department of Education fellowship to design a “breakthrough model” school. He and a cohort of other educators designed a model they thought would create radically different outcomes for low-income teens. They planned to implement the model in four district schools and four charter schools.

“Every team member was excited about schools opening in both policy environments, Clemente said. “The idea was to surface the policy constraints that arise in each and to leverage the strengths in each.”

In the end, they were only able to open three district schools, Nelson Mandela School for Social Justice, Epic North, and Epic South, and one charter school — South Bronx Community Charter. Clemente says his goal is to return to the original mission of charters, incubating ideas that can be spread to district schools.

Perhaps one of the most radical aspects of the school is its commitment to restorative practices. Clemente noted that on a heat map of suspensions published by Chalkbeat, the South Bronx is deep purple. Students and families expect to be suspended, but educators at this school have worked hard to change the narrative and show with their actions that they want every child to stay in school.

“Our students come in with a lot of trauma that’s coming in from the community,” Clemente said. “It takes a lot for us to build community with them so they can trust school as an institution.”

In the first week, in their first year as a school, a student got jumped by a group of other students for throwing a gang sign. That was the first test of the school’s commitment to restorative practices. The mother of the kid who was attacked wanted the perpetrators suspended. Clemente told her that wasn’t off the table, but he wanted to try something else first.

They asked the boys to write apology letters to both the kid they jumped and his mother. Then they had to stand in the middle of a circle of their entire grade, explain what they did, and ask the community for forgiveness. At this point the whole school was just one grade, 100 kids, small enough that everyone discussed the incident together. Each student had the chance to express how it made them feel. “And we never had another fight that year,” Clemente said.

Chris De La Cruz knows the impact of that moment went even deeper. One of the main perpetrators was one of his advisees. When the leadership handled the incident restoratively, the student saw they were committed to him. Now he’s the one spreading the message among peers not to fight, that conflicts can be handled nonviolently.

“A lot of aggression happens because there’s been a lot of aggression towards them,” De La Cruz said. He doesn’t think schools acknowledge often enough the structural influences and systemic oppression that students experience throughout their lives.

“It’s not that we’re saying you’ve made mistakes, it’s OK,” De La Cruz said. “It’s more like, you’ve made a mistake and we’re not going to kick you out of the school. That’s where real learning happens.”