MLK Day post turns public attention to Montana

Author: Greta Anderson

Go to Source

The University of Montana was in the early stages of addressing complaints about the lack of racial diversity on campus when it decided to hold an essay contest marking Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

The contest was seen as an opportunity to engage students of various backgrounds and spur dialogue across the campus about the life and work of the late civil rights leader. But the plans backfired when the university announced, and proudly promoted, the four winning essays — all penned by white students.

The backlash on social media was swift and searing and, perhaps most interestingly, multiracial.

More than 1,100 commenters, many of them self-identifying as white, took to Facebook to call out university officials for being “tone-deaf” and “shameful” and criticizing the contest as a “colorblind mess.”

The critics questioned how the selection committee could think it appropriate to move forward with the contest after only getting six entries, all submitted by white students.

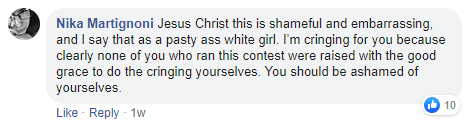

“Jesus Christ this is shameful and embarrassing, and I say that as a pasty ass white girl,” said one commenter. “I’m cringing for you because clearly none of you who ran this contest were raised with the good grace to do the cringing yourselves. You should be ashamed of yourselves.”

“Jesus Christ this is shameful and embarrassing, and I say that as a pasty ass white girl,” said one commenter. “I’m cringing for you because clearly none of you who ran this contest were raised with the good grace to do the cringing yourselves. You should be ashamed of yourselves.”

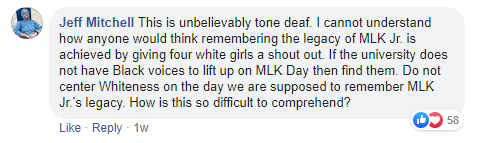

Another poster said he could “not understand how anyone would think remembering the legacy of MLK Jr. is achieved by giving four white girls a shout out. If the university does not have black voices to lift up on MLK Day, then find them.”

Another poster said he could “not understand how anyone would think remembering the legacy of MLK Jr. is achieved by giving four white girls a shout out. If the university does not have black voices to lift up on MLK Day, then find them.”

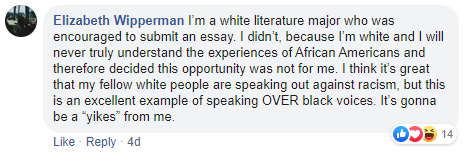

Elizabeth Wipperman, a senior majoring in literature, said she was encouraged to write an essay but decided not to.

Elizabeth Wipperman, a senior majoring in literature, said she was encouraged to write an essay but decided not to.

“I will never truly understand the experiences of African Americans and therefore decided this opportunity was not for me,” Wipperman wrote on Facebook. “It’s great that my fellow white people are speaking out against racism, but this is an excellent example of speaking over black voices. It’s gonna be a ‘yikes’ from me.”

The reaction was not quite the unifying exercise that university officials might have wished. Instead, it amplified students’ awareness of the social and racial challenges playing out on the campus in Missoula and at other colleges and universities around the country.

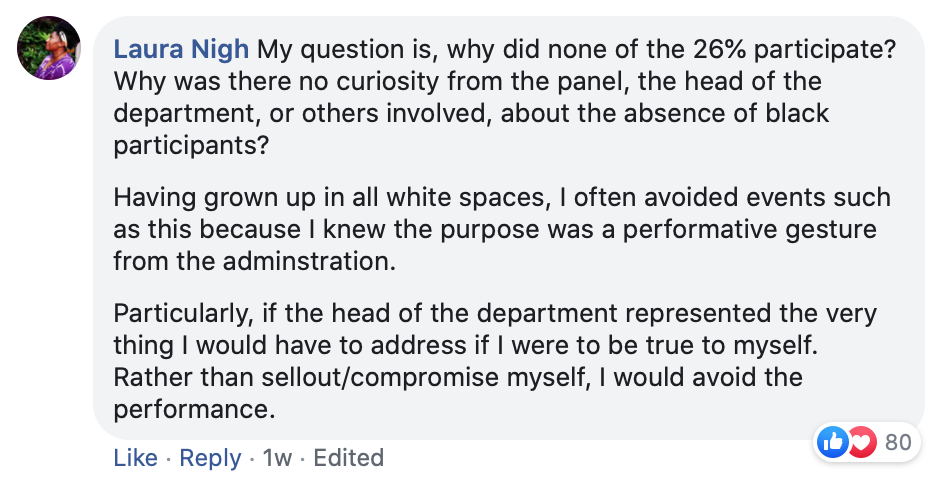

“Why was there no curiosity from the panel, the head of the department, or others involved, about the absence of black participants?” a black commenter asked in a Facebook post. “Having grown up in all white spaces, I often avoided events such as this because I knew the purpose was a performative gesture from the administration….Rather than sellout/compromise myself, I would avoid the performance.”

Some of the fallout turned ugly and caused University of Montana officials to take down pictures it had posted of the four young women who won the contest, along with excerpts of their essays.People had started posting threats against them.

At the majority-white university, where less than 1 percent of undergraduate students enrolled in fall 2019 were black and about 1.3 percent were Asian and 5.4 percent Hispanic or Latino, the contest reflected a lack of representation that many students of color feel on campus, said Marcos Lopez, a member of the Nez Perce tribe and president of the Kyiyo Native American Student Association. (Native American or Pacific Islander students were 3.8 percent of undergraduates, according to the Office of Institutional Research.)

Lopez said students of color struggle to have their voices heard and needs met. He noted, for example, the understaffed American Indian Student Services office, which provides academic and financial aid advising but is often unable to schedule student appointments in a timely manner. The lack of diversity among faculty members and administrators — the faculty is nearly 90 percent white, according to data provided by the university — and the absence of a chief diversity officer or an office focused on diversity and inclusion has created a disconnect between students and university leaders who “can’t relate with us in a way that’s meaningful,” he said.

Failed Strategy to Connect

The purpose of the contest was in part to encourage participation across the entire campus, not just by students of color, and to challenge them to ask, “What can I do to fight racism?” said Tobin Miller Shearer, the MLK Jr. Day committee chairman and director of the African American studies program.

Miller Shearer, who is white, said students of color have told him that the responsibility of addressing issues of racism too often falls to them.

“We were wanting to engage white people and students of color,” Miller Shearer said. “It was students of color saying that they did not want to do the heavy lifting.”

The deadline for the essay contest was on the final day of the fall semester. The winners were posted on the university’s Facebook account on Jan. 20, the national holiday celebrating King.

Lopez, whose organization holds the annual Kyiyo Pow Wow on campus, one of the university’s largest cultural events, said he and others were not even aware of the contest until the winners were announced. Lopez did not see the purpose of a contest about fighting racism if it did not include people of color. He said the contest deadline should have been extended so more people could have entered and that the all-white roster of winners should not have been publicly announced.

“The meaning of Martin Luther King Jr.’s life work isn’t going to be as significant to somebody who is from a privileged background,” Lopez said. “It doesn’t affect the day-to-day lives of white people as much as it does people of color, who historically have faced oppression in their daily life.”

Shaun Harper, executive director of the University of Southern California’s Race and Equity Center, said it was a positive sign that white students participated in the contest.

“It is totally fine and appropriate and good for white people to write about the legacy and impact of Martin Luther King Jr. and their understanding of King’s contributions to social justice,” Harper said. “I would go so far to say I wish we had more white students in college who would and could take the time to articulate King’s impact on social justice.”

The center’s research includes campus climate studies in which white students report a lack of opportunities for them to develop an understanding of racial justice.

“We send millions of white college students into the world without the study of racial justice and equity topics,” Harper said.

Although the MLK Day committee’s efforts were well intentioned, Miller Shearer said the group considered tossing out the contest when they saw the results. He said the decision to post the winners was a “judgment call” made by the committee, comprised of five people of color and four white people, including the presidents of the Black Student Union and the Latinx Student Union. They were disappointed with the pool of six white applicants and knew the ethnicity of the winners would be “problematic,” Miller Shearer said.

“Whether we made the right decision or not is certainly open to debate,” he said. “What we finally decided was that even though this would be uncomfortable, it is to a degree a reflection of the university and it would create a base to work from.”

The “unfortunate profile” that was created of the essay-writing contest on social media overshadowed many of the other ways students of color celebrated King, Miller Shearer said.

Reassessment and Repercussions

Lost in the debate over the contest is that it “was but one opportunity among many to celebrate the life and legacy of Dr. King” and “several students of color chose to direct their efforts in other quarters,” said Murray Pierce, a student affairs official who serves as adviser to the BSU and mentor to black students. He noted that some of those students participated in a youth rally in the Missoula, Mont., community or attended a discussion on King’s legacy led by Meshayla Cox, a Montana alumna and outreach coordinator for the Montana Racial Equity Project.

BSU members are also preparing for their third annual Black Solidarity Summit scheduled for Feb. 15, where they will host students from BSUs across the Pacific Northwest and elsewhere in the U.S. to discuss and plan how to “move the dial” on issues of diversity and inclusion on college campuses, Murray said. Natasha Kalonde, the BSU president, did not respond to requests for comment.

Judith Heilman, executive director of the Montana Racial Equity Project, said the University of Montana’s failure to mention these other initiatives and events in its MLK Day Facebook post focused attention on the efforts of white students and excluded the activities of students of color.

“The post should’ve been about lifting the voices and the unity of the Black Student Union and black students on campus,” said Heilman, who is African American. “The writing contest was a very small part of what UM was doing for Martin Luther King Jr. Day, but the other parts of it weren’t shared.”

Rosemary Lytle, president of the Colorado, Montana, Wyoming State Conference of the NAACP, criticized the decision to move forward with “a poorly advertised, poorly publicized” contest “with no targeted marketing of any kind to black students or students of color.”

Lytle said the excuses committee members provided for the low participation in the contest did not “ring true” because there were many indicators that it would not be representative of the university.

“The university, which has a nonblack director of African American studies, decides that there must be an MLK essay contest despite the fact that students of color and black students specifically are overcommitted during this time, where observances and celebrations of black life, black achievement are plentiful,” said Lytle.

The committee is examining how the essay question, which had separate entry categories for students, faculty members and staff and asked how they are “implementing Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy” on campus, may have contributed to the low participation by students of color, Miller Shearer said.

Mariah Omeasoo, a member of the Blackfeet tribe and vice president of Kyiyo, said she decided not to participate because she isn’t black.

“I felt like it wasn’t my place,” she said, adding that she understands King would likely lift up the voices of other people of color, not just African Americans.

Lawrence Ross, who speaks widely about racial issues on college campuses and is author of Blackballed: The Black and White Politics of Race on America’s Campuses (St. Martin’s Press, 2016) said the university erred by using a contest format to engage a diverse group of students with vastly different perspectives.

“Sometimes when people view contests like this, they’re thinking there’s a universality around writing an essay. Maybe there’s not,” Ross said. “How the black students express themselves is completely different from the Native American students and the Latinx folks. That should be the focus — how do we come together from our various perspectives?”

Lopez, the president of the Native American student association, noted that the university did not make a direct effort to make students in Kyiyo aware of the essay contest. A university spokesperson said the contest details were sent to all students in a weekly email newsletter.

But if the intention is to engage a diverse group of students, a universitywide email is not good enough, Harper said.

“It would be a huge missed opportunity for this university to see this as an isolated incident and focus all its effort on getting more applicants next year,” Harper said. “It would shock me if this was the only space where there was woeful participation, or in this case no participation, of students of color in a space.”

Students of color have formed their own communities on campus through student organizations in which they feel listened to and understood, Lopez said.

“African American and Latinx students face the same issues,” Lopez said. “There’s something comforting about being around each other, so we certainly get together as much as we can. It’s a struggle when there’s not a lot of our identities reflected in the institution.”

Work in Progress

Seth Bodnar, the university’s president, has heard suggestions from a Diversity Advisory Council to hold meetings with students and determine what resources a student-centered diversity and inclusion office or director would provide, Paula Short, director of communications, said in a university statement. Discussions about creating such a role or office are scheduled to begin this week between student affairs officials and organizations that represent students of color, Lopez said.

The university is also in the process of creating a new position for a diversity, equity and inclusion specialist in the human resources department to focus on recruiting more diverse faculty and staff and providing sensitivity training to current faculty members, Short said.

“We recognize that we have much more to do,” Short said. “In response to calls for institutional attention to issues related to diversity, President Bodnar is working to better understand the current diversity and inclusion landscape at Montana and to identify needs and gaps.”

Lopez said students will turn to activism if there is no progress on addressing these issues.

“Through those conversations, hopefully something comes about if we go in and present our feelings and what we’ve experienced,” he said. “But if we go in there and nothing happens, then yeah, we’re going to protest.”