The Conference Board’s 0-4 on Innovation Policy

Author: Stephen Downes

Source

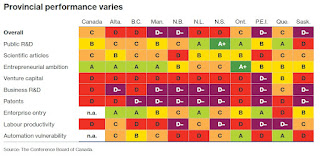

The Conference Board of Canada makes four recommendations for innovation in Canada. It’s based on a self-styled ‘report card’ that ranks Canada as a ‘C’ on innovation (the U.S. and Switzerland rank ‘A’, which should tell us something). In my opinion, they are wrong across the board, make the same old tired mistakes that have led us nowhere in the past. I’ll deal with each in turn.

1. Continue Stimulating Spending on Innovation

Let’s note immediately that ‘stimulating spending’ is different from ‘spending’. The word ‘stimulation’ is code for ‘financial incentives’, ie., directing public money to private enterprise. The Conference Boad discussion makes that clear.

The report notes,

Canada and many of the provinces have performed well on public research and development (R&D) in the past; however, spending as a share of GDP has slipped over the past decade.

That to me suggests that past policy has been failing. So why would we continue that policy?

Here are the Board’s specific recommendations, and my responses:

- investigate whether the current mix of tax incentives and direct support stimulates spending and investment

I think we already know the answer to that question: it doesn’t. Otherwise our continued and generous spending on tax incentives and direct support would have had a positive impact, rather than the negative result we have observed. We know what happens: companies take the money, and then do what they were going to do anyways. In the case of multinationals, this means directing revenue to research and development in other countries (and particularly the U.S.). I mean, I’m not saying we shouldn’t continue to track the data. But the data so far from the last 20 years or more are pretty clear.

- examine how structural features of national and provincial economies affect spending on business R&D and technology

We will need to defer discussion here until we know what sort of ‘structural features’ they have in mind.

- explore new ways to improve spending—including looking at practices in top-performing countries

It’s significant to note that instead of looking at who gets funded, the Conference Board is more concerned about what gets funded. Note that the presumption here is that we should spend (and by implication, spend directly on private sector companies). Improving that spending is always an option – but again, what would we be doing that we haven’t been doing over the last 20 years? Our history is a long track record of trying to emulate U.S. and European innovation policy.

Instead of spending on research and development initiatives that benefit (specifically selected and targeted) private capital, we should be spending on developing an advanced research and development infrastructure in Canada. Some reasons why:

- You can’t simply acquire the infrastructure and move it out of the country

- It provides opportunities for new and innovative companies, not only to entrenched business looking to protect market share (as an aside, and as an example: consider how important a public health care system is to enabling people to leave employment and pursue a start-up idea)

- It provides access to non-commercial and public services oriented organizations (including all levels of government) and not only private enterprise

2. Improve Technology Adoption and Use

Digital technologies provide the necessary infrastructure to exchange ideas and share data within and across organizations… There are many barriers to digital technology adoption, including costs, integration time, training requirements, a lack of usability and compatibility, regulatory frameworks and trade barriers, a lack of knowledge and trust in digital solutions, and a limited number of employees with the appropriate skills. Governments should address these barriers to support and incent businesses to innovate.

Not to make too fine a point: the idea here is to fund businesses that for some reason have not been investing in digital technology adoption over the last 20 years. One wonders, where were they over all that time? Under a rock? Why should we spend money supporting businesses that missed the most obvious trend in the last millennium?

By analogy: when the automobile was developed, some companies invested in vehicles, and some didn’t. The Conference Board’s recommendation is to fund companies that didn’t invest in vehicles. My response is that a better allocation of funds would be to develop the public road infrastructure. Because again, we should be spending on infrastructure that benefits forward-looking people and organizations, not on companies that are 20 years behind the curve.

3. Create a healthy business environment

The board likes to use the word ‘healthy’ as a proxy for the word ‘favourable’. However it should be clear that what is favourable for business is not always healthy for society as a whole.

The Board says specifically:

- a healthy climate for new ventures, including adequate market demand and access;

- strong and reliable supply chains, transportation, and communications infrastructure;

- favourable tax rates and tax regime clarity;

- appropriate regulation;

- access to capital and expertise;

- an appropriate mix of core capabilities.

Policy-makers have levers to address some, though not all, of these factors.

There’s a lot packed into this short list, and it reflects the common lobbying points that businesses have presented (and mostly received) to government over decades. Many of these phrases have become shorthand for very specific demands:

- The phrase ‘adequate market demand and access’ means that government should support privatization of key public services where possible, and where not possible, either engage in public-private partnerships (PPP) or outsource goods and services to private industry rather than producing them as government services. There’s a lot that’s wrong with this, including the huge and demonstrable inefficiencies it creates, as well as the requirement for oversight and accountability. The list of private sector procurement initiatives that have gone south is almost endless. But the main point here is that the purpose of government programs is to provide services, not to create markets for the private sector.

- The phrase ‘favourable tax rates’ means zero or low taxes on private enterprise. Competing with the rest of the world on the basis of low taxes is essentially a non-starter; even if the Canadian tax rate were zero, this would not result in sustained economic growth or business development. This is because tax rate isn’t the major factor in where businesses develop and grow. Businesses are much more concerned about things like labour market, social infrastructure, public security and stability, and other public services. They just don’t want to pay for them. But they should.

- By ‘appropriate regulation’ businesses generally mean ‘deregulation’, because regulation makes it harder to sell low quality goods and services (especially to government) at premium prices. It should be clear that when a business wants something deregulated, it’s because they want to engage in that particular practice: dumping pollution into the river, discriminating against minorities when hiring, selling unsafe safety equipment, etc.

There’s a lot more here, but I think it should be clear that (a) businesses don’t really need these things, (b) there merely want them, but (c) the social cost of granting them is often (much) greater than the benefit of granting them.

4. Improve resiliency to automation

I would have thought this recommendation would have been something along the lines of benefiting from the increased productivity automation enables, but again, business often prefers to protect existing business models and practices rather than to develop something new.

Anyhow, the Board says,

Placing automation in the context of other ongoing labour market trends highlights additional vulnerabilities that the provinces will likely face as companies and industries adopt new automation-enabling technologies. Knowing the type and amount of employment at risk of automation—and the economic cost associated with potential transitions to less-vulnerable occupations—could help policy-makers better prepare for technological change.

It will also help the provinces equip their workforces with the skills and resources necessary for businesses to increase and sustain their innovation activity.

So, what businesses want is a workforce that can manage increased automation. But they don’t actually want to invest in this – that’s why at this point they recommend ‘the provinces equip their workforces’. That is, the provinces’ workforces. It’s up to the provinces to train them. The more the better, because a surplus will keep wages lower. Then they’ll harvest that investment for themselves (and probably complain that the provinces didn’t do a good enough job).

What society wants from automation, I would say, is for all of us to benefit from increased productivity. But that means not only helping people develop higher level skills but also helping them directly benefit from those skills. This means a lot more than just skills development for employment. It means creating an environment and social infrastructure where people have options, mobility, and the means to negotiate for a greater share of that increased productivity. Most businesses won’t support that sort of learning and development, because it runs counter to their own short-term interests.

Coda

The Conference Board’s discussion and recommendations are essentially advocacy for a set of policies that have benefited businesses and enriched a small number of people, but that have failed to produce lasting benefits for Canadians, much less a sustainable response to rapidly changing economic conditions. Even if business benefits from these government policies, the wealth will not trickle down to individual Canadian communities and citizens. As a result, the Board’s recommendations are, in the main, harmful to the interests of Canadians, and should be challenged.